An Analysis of the USDe Price Dislocation Incident on Binance

1. What Does “Peg” Truly Mean in Stablecoins?

In crypto markets, “depeg” usually refers to a stablecoin’s price falling below one dollar. However, the real meaning of the “peg” lies not in the price itself, but in the integrity and redeemability of the assets backing the stablecoin.

In other words, what is anchored is credit, not price.

Taking USDe as an example, its redemption channels remained fully operational during the incident, with over two billion dollars redeemed. From that perspective, USDe’s anchor never broke.

Prices on-chain and across most exchanges quickly returned to around one dollar after brief volatility. Only Binance experienced a longer-lasting price distortion. The 0.65 USD price was not a sign of systemic depegging but a localized pricing dislocation caused by structural liquidity imbalances.

This situation resembled temporary liquidity vacuums seen in volatile altcoins rather than a full-scale credit collapse. The logic differs fundamentally from previous stablecoin failures.

2. Why Can Prices Deviate Even When the Peg Is Intact?

Even when a stablecoin has full collateral backing, secondary market prices are still driven by supply and demand. In theory, different stablecoins are not naturally interchangeable. Their one-to-one relationship is maintained through several interconnected mechanisms.

(1) Redemption Mechanism

Each USDe token is backed by redeemable assets, and the official redemption system continued to operate normally.

However, similar to other regulated stablecoins, minting and redemption are open only to whitelisted institutions. Retail users rely on secondary markets and on-chain pools for liquidity, not direct redemption.

While this differs from decentralized stablecoins such as DAI, institutional redemption still maintains peg confidence, with redemption prices reflected in oracle feeds.

(2) Liquidity Depth

Price stability depends heavily on market makers placing orders at key levels. After Binance launched leveraged looped lending with USDe, supply expanded rapidly while market-making depth did not grow proportionally. This imbalance created the conditions for later price instability.

On-chain liquidity incentives do not directly affect centralized exchanges, so they could not mitigate the issue.

(3) Arbitrage Mechanism

Professional arbitrageurs usually bridge price differences across platforms, ensuring secondary market stability. When liquidity or redemption becomes limited, arbitrage activity weakens and prices can deviate.

Any failure in these mechanisms, redemption, liquidity, or arbitrage, can cause temporary dislocations. In the Binance case, both liquidity and arbitrage channels failed at the same time, creating a closed-loop market where prices diverged for over an hour.

3. What Exactly Happened?

The direct trigger was Binance’s looped lending mechanism, which allowed users to deposit USDe, borrow assets, repurchase USDe, and repeat. This recursive strategy created leveraged exposure and amplified returns.

Because borrowing rates were temporarily lower than the protocol’s yield, some users expanded their positions aggressively, with leverage reaching more than 3.5 times. This feedback cycle can generate short-term prosperity in calm markets but accelerates collapse during volatility.

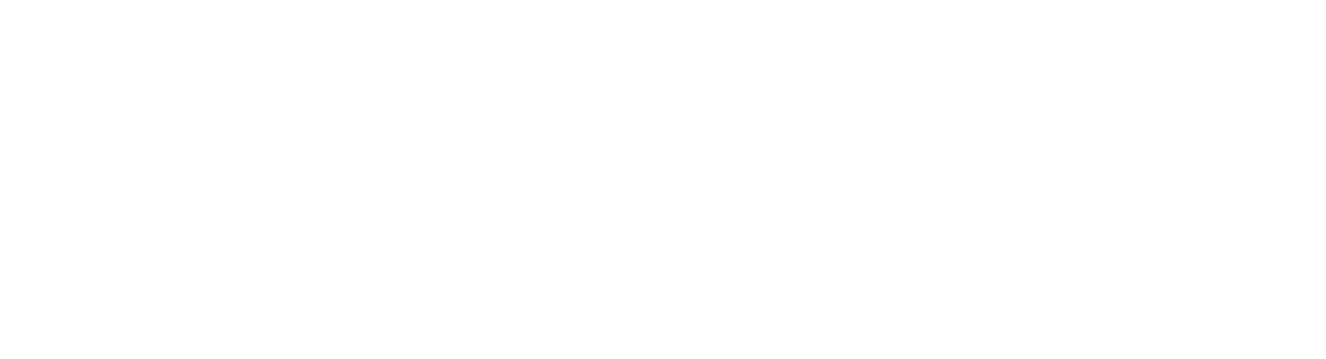

The sequence unfolded in seven stages:

- Risk Accumulation. USDe became a popular leveraged asset on Binance, leading to excessive reuse of collateral without proportional liquidity growth.

- Macro Shock. On October 10, the “Trump tariff” news triggered a broad sell-off, causing margin stress for USDe’s delta-neutral hedging strategy.

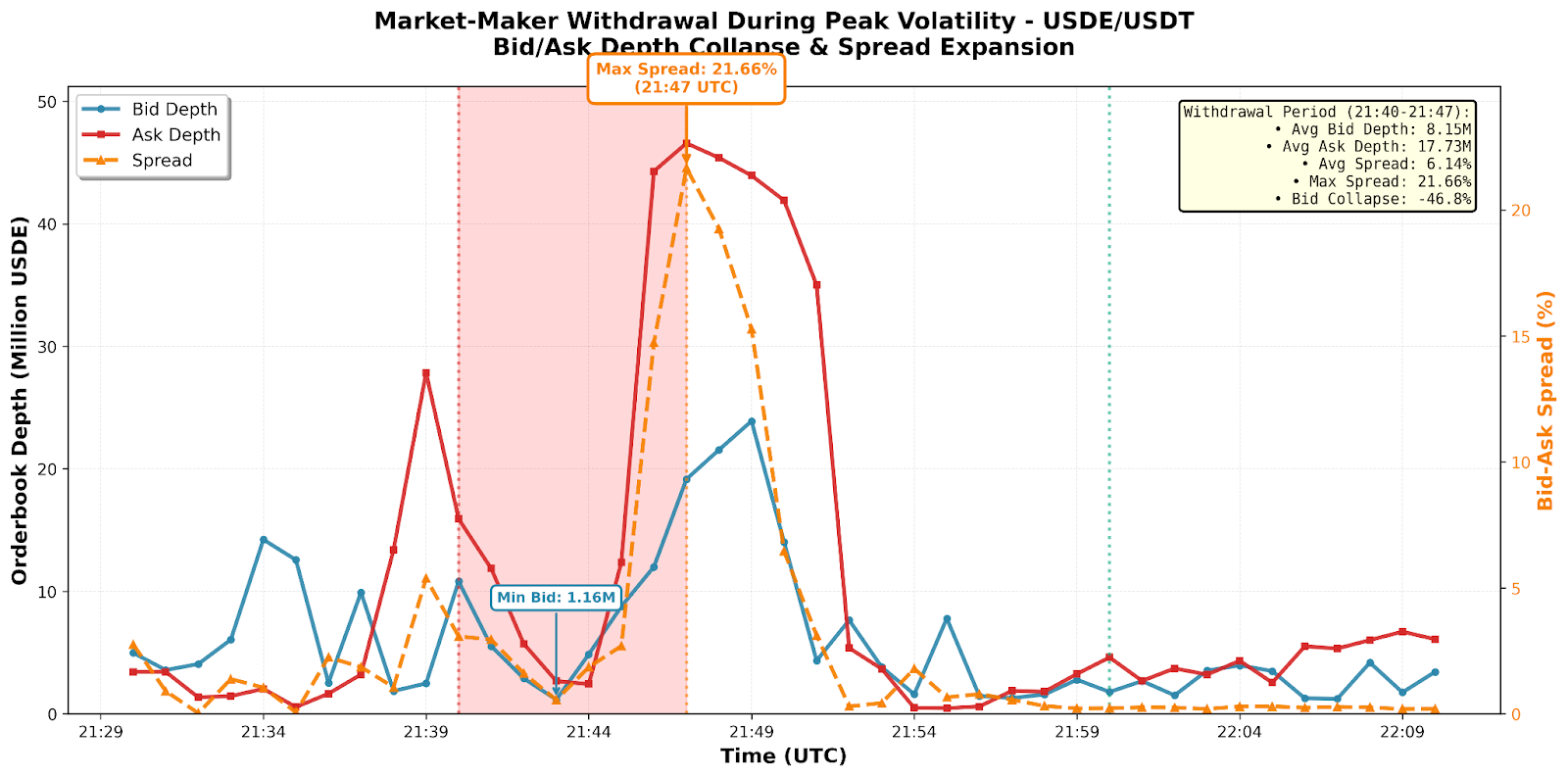

- Liquidity Collapse. Market makers withdrew orders, leaving large gaps in the USDe/USDT order book.

- Forced Liquidations. As prices dropped, margin calls and forced sales overlapped, deepening the decline.

- Oracle Feedback Loop. Binance’s internal oracle referenced its own price feed. As prices fell, liquidation thresholds triggered further selling, creating a feedback spiral.

- Arbitrage Breakdown. Binance suspended USDe deposits and withdrawals, isolating its market. Cross-platform arbitrage stopped, turning Binance into a closed “price island.”

- Price Recovery. Several hours later, withdrawals resumed. Arbitrage activity returned, and prices quickly recovered to above 0.99 USD. The rebound, however, relied on external liquidity rather than internal balance.

This was not a credit collapse of USDe itself, but a liquidity vacuum within the platform. On-chain and other exchange prices stayed near one dollar, while Binance’s isolated market diverged for over an hour.

4. Conspiracy or Structural Weakness?

There is no evidence that this was a coordinated attack. The October 10 market shock originated from a broad macro event, not a single entity.

However, the incident exposed a key reality: when liquidity dries up, arbitrage halts, and withdrawal channels close, centralized systems amplify volatility.

Several Binance factors worsened the impact, including reliance on a single internal price oracle, suspension of deposits and withdrawals, and a liquidation mechanism that compounded selling pressure.

The deeper cause lies in Binance’s looped lending structure, which magnified leverage and risk. The event therefore highlighted not the weakness of the stablecoin itself, but the vulnerability of centralized trading systems under stress.

Although investors suffered temporary losses, prices later normalized. Binance compensated some users affected by mispriced liquidations, but the wider consequences remain unclear.

5. Inherent Risks in USDe’s Design

Although the event did not result from a failure in USDe’s core design, derivative-backed stablecoins still face structural risks.

(1) Scale Constraint

Each USDe token corresponds to a delta-neutral short position on a major crypto asset, functioning as a neutral fund share. The model’s profitability depends on moderate scale. If supply grows to hundreds of billions, funding rate dynamics could shift, undermining returns and stability.

(2) Trading Mechanism Risks

USDe’s neutrality relies on stable perpetual futures markets. Problems can arise when auto-deleveraging cuts profitable shorts, breaking neutrality, or when funding rates stay negative for prolonged periods, turning yield into loss.

Ethena, USDe’s issuer, has implemented safeguards, but these remain to be tested under long-term stress.

(3) CEX Interaction Risks

USDe’s hedging strategy depends on centralized exchanges for execution and custody.

Potential risks include exchange failures or downtime that freeze positions, custody risks such as hacks or operational errors, and policy changes affecting margin or leverage rules, which can distort hedging efficiency.

These dependencies underline the paradox of a “decentralized” stablecoin that still relies on centralized infrastructure.

6. Liquidity Management for Emerging Stablecoins

New stablecoins are reshaping investor behavior through diverse mechanisms. Their anchors vary widely.

USDe operates as a delta-neutral yield product. DAI is a crypto-native on-chain collateralized asset. OpenEden’s USDO, now listed on Binance, is linked to real-world assets and generates yield.

As such assets expand, effective liquidity management becomes critical.

Emerging stablecoins should strengthen depth with established peers such as USDT and USDC, which remain benchmarks of stability. When one USDe trades at 0.65 USDT, no one questions USDT’s price integrity.

Developers must focus on reliable depth management, larger liquidity providers, and tighter spreads. Stablecoins are ideal products for market makers because inventory risk is minimal. Direct cooperation between whitelisted institutions and market makers can further reduce panic-driven outflows.

Additionally, on-chain liquidity incentives should encourage LP participation to ensure robust, system-wide liquidity.

7. Conclusion

The USDe incident drew widespread attention, even beyond the crypto community. This demonstrates that stablecoins are no longer niche instruments but have entered mainstream financial discourse.

This is ultimately positive. The market is educating itself while exploring the limits of a new financial order.

Despite short-term volatility, the structural takeaway remains clear. USDe’s redemption and collateral mechanisms held firm. This represents progress from algorithmic narratives toward engineering-based stability.

At the same time, this event reminds all new stablecoin projects that risk control and liquidity management are not auxiliary functions but essential foundations.

In an increasingly complex market environment, transparent risk frameworks, layered liquidity networks, and co-existence with legacy stablecoins will be the pillars of a resilient and prosperous crypto economy.

Media

Ideas & Inspiration

Polymarket---The On-Chain Prediction Market Pricing the Future

The Structural Logic of Yield-Bearing Stablecoins

LADT Launch | OOKC Drives Digital Economy Growth